Albert Chamillard’s Abstractions

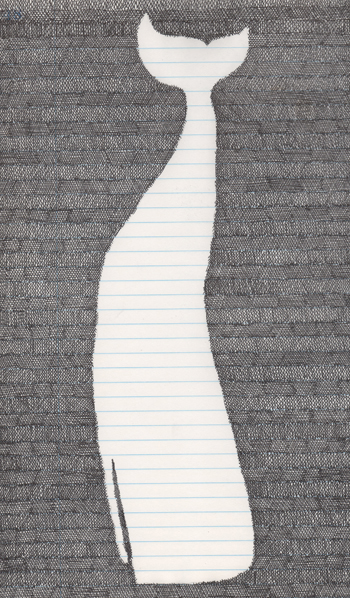

“Descending Whale 148” by Albert Chamillard

Albert Chamillard slowly builds his drawings, layering thousands of small precise marks until the form takes shape.

His style–patient, reflective and emblematic–emerged over time. As an art student at the UA, Chamillard concentrated on larger works, four-foot by five-foot, with bold charcoal drawings. After having kids, he says it became harder to get out of the house and go to his studio to do that kind of work, so he began working on a smaller scale, at night, at his kitchen table.

“These works sprang out of notebooks. They all start out small-scale and I slowly start building them,” he says.

Chamillard’s drawings are of a range of subjects, often times geometric abstractions, speech bubbles or figurative drawings of whales. They’re heavily layered, heavily marked and very graphic, yet sparse. His work reads almost like text, with horizontal lines of markings built on top of one another. Often times, he will experiment with an image and its reverse.

“Being a figurative artist and experimenting with abstraction, I’ve always liked the idea of people saying ‘My kid could do that.’ I want the drawings to look simple on first appearance and then draw you in further,” he says.

Chamillard begins with a first layer, done in a herringbone pattern of back and forth slashes. For the second layer, he makes another pass, reversing each mark for an X pattern. For the third layer, he places horizontal and vertical lines on each. The left-handed artists rests his hand on an envelope to keep the ink from smudging as he slowly adds layers, building contrasts into his conceptual work. The detail in the finished product can be similar to the eye-trickery of optical illusions.

“It does something with your eye where it looks a bit blurry and it gives it some movement,” he says. Chamillard, 42, moved to Tucson in 1994 and earned his BFA in 2003.

Though Chamillard’s work is conceptual, there’s an idea behind each drawing. The whale motif is biographical, representing his upbringing in Massachusetts. The speech bubbles come from a fascination he has with how speech is depicted in art. As for abstractions, he’ll experiment with different forms to find what looks good on the page.

Much of the meaning in his work derives from what Chamillard is thinking about while he’s at work on a piece, which takes about 30 to 50 hours for his current full-size drawings. For instance, one piece is about his relationship with his brother, though he doesn’t tend to make the meaning explicit.

“I don’t want to put that idea into people’s heads. All of my stuff is deeply personal. I’m reflecting and thinking about stuff as I work. They carry a lot of emotional weight for me, but it’s not always that obvious,” he says. “It’s good to be in touch with your work and how it relates to you personally.”

Art has been the focus of Chamillard’s life, something he always knew he could do. He knew also that a career as an artist would be a struggle, so he persisted in finding ways to make it happen. And while he’s had other jobs in galleries and frame shops most of his adult life, Chamillard’s latest work has connected with people to the point where he can pay all his bills through his art alone.

“For whatever reason, people really respond to this work. This has launched a whole new part of my career,” he says. “You reach a point where you just let go and make stuff for yourself to enjoy and people really respond to it.”

Chamillard’s work will be part of the Davis Dominguez Gallery’s Small Things Considered show, the small-works invitational running from May 8 to June 28 at 154 E. 6th St.

“I try to make stuff that looks beautiful and is enjoyable for me to make. You start to question it too much and that just gets in the way,” Chamillard says. “There’s a human act called art, and I’m a part of it. I understand the compulsion to do it. It’s a way of responding to your world.”

Chamillard’s work is also shown at the Eric Firestone Gallery in East Hampton, NY. Chamillard used to work for Firestone’s Tucson gallery and after Firestone moved to New York, Chamillard opened Atlas Fine Arts Services with James Schaub in 2011, which recently closed. See related story on page XX.