An Excerpt from Tucsonan Lydia Millet’s New Novel

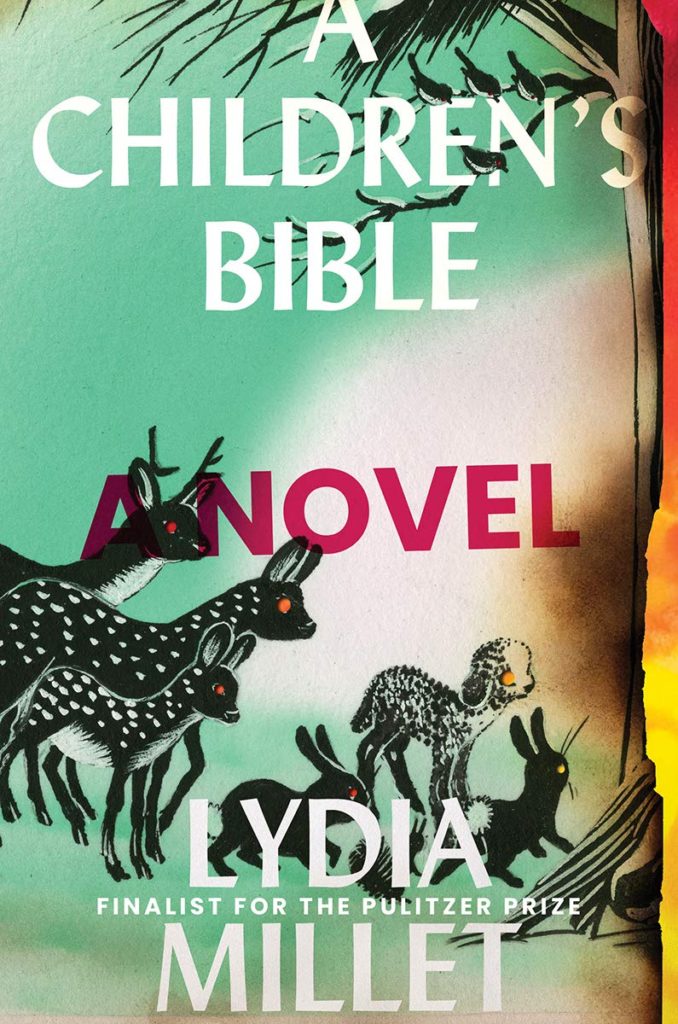

A Children’s Bible

Lydia Millet has lived in Tucson since 1999, a year before her second novel, George Bush, Dark Prince of Love, appeared. In the years since, while working as a writer and editor for the Center for Biological Diversity, she has published 16 more books of fiction for young and adult readers. Of her latest, A Children’s Bible (Norton, $25.95), Washington Post books editor Ron Charles writes, “I swear on a stack of copies that it’s a blistering little classic: ‘Lord of the Flies’ for a generation of young people left to fend for themselves on their parents’ rapidly warming planet.” Alternately dark and comic, it’s told from the point of view of a young woman who grows to maturity in a time that, like our own, is full of threats and terrors—but also great beauty. Copies of the book are available at Antigone Books (411 N. Fourth Ave.); call 792-3715 to reserve your copy for curbside pickup. Evoking a world of missing things that is all too recognizable, here’s a glimpse inside the covers. —Editor

By late winter all the vegetables we ate were coming from the hydroponic nursery and the indoor garden in the basement (what used to be the squash court). Fresh produce could no longer be ordered online—no refrigerated trucks were running, at least not for the average rich person in our neck of the woods—so we had to eat what we grew.

We didn’t have fruit, of course. We’d planted apple trees, but it’d be years before they were fruit-bearing: that planting was a Hail Mary. No citrus at all, and we missed our orange juice and lemonade. The parents missed their slices of lime.

And we had dry and canned goods, a trove far more extensive than the one in the silo. We had made sure of that.

When the day’s work was done we got into the habit of preparing dinner for everyone, with the help of some mothers whose highest-rated skills were cooking. We’d all sit around in the vast sunken living room of fake Italy, with its wall of glass that opened onto the patio and the pool. We held our plates on our laps, eating and talking about the things we missed. The peasant mother was allowed to recite a blessing. Nondenominational.

She’d turned out to be no one’s mother at all. All she had was the cat. But I still thought of her as the peasant one.

Then we’d go through our missings. That was what my little brother called them. We figured it was healthy, for the parents especially, not to try to deny the fact of what had been lost but to acknowledge it.

Someone would mention a colleague or an ex, a grandparent or a bicycle or a neighborhood or a store. A beach or a town or a movie. Someone would say “ice cream” and someone else would say “ice-cream sandwiches, Neapolitan,” and we’d riff on it, go down a list of favorite ice-cream novelties that couldn’t be had anymore for love or money.

“Bars,” a parent would say, and they’d rhyme off the bars they’d been to, the dive bars, the Irish bars, the cantinas. The hotel bars, the bars with jukeboxes, the bars with pool tables or views of parks and rivers. The bars that revolved. The bars at the top of glittering skyscrapers far away. In the once-great cities of the world.Excerpted from A Children’s Bible: A Novel by Lydia Millet. Copyright © 2020 by Lydia Millet. Published with permission of W. W. Norton. All rights reserved.