Tucson COVID Tales No. 14: My COVID Experience, by Richard A. Dooley

I began writing this in a hotel room in Kalispell, Montana, while my wife, Vonnie, and I were on a two-week road trip through Utah, Washington, Montana, and Colorado. I needed this trip, and we needed this vacation. We realize that traveling from Arizona through these states might be ill advised, given Arizona’s surging coronavirus status. But after much consideration, we felt that traveling in the sealed capsule of a car on the open road was an effective method of physical distancing. In the 14 days we were gone, we’d eaten indoors in only two restaurants. We had breakfast at Stella’s in Billings, Montana, and were pleased to see that Stella and her crew had distanced the tables and that all staff were wearing masks. We did not expect this, but to be honest, we didn’t know what to expect. Customers even wore masks until they were seated. I was proud of Billings. In Bonners Ferry, Idaho, we stopped for gas and not a soul was wearing a mask.

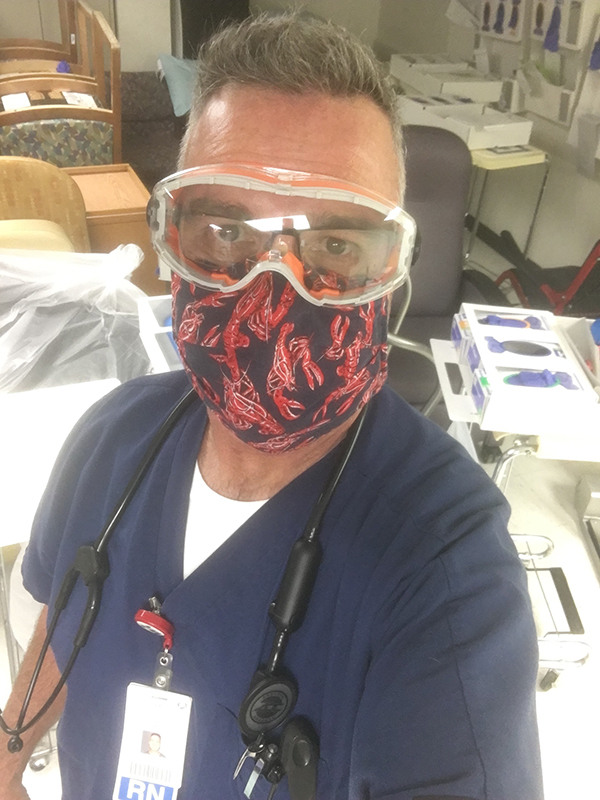

I have a personal stake in masking, social distancing, and all the rest of the measures responsible people are taking to combat the coronavirus. On March 25 and 26 of this year I was exposed to COVID-19 via a patient I cared for as an RN on the telemetry unit at a Tucson hospital. In the last few hours of my shift on the 26, I started sneezing and experiencing a runny nose. I thought little of it since Tucson had recently had some rain and the wildflowers were showing up in force. Every year, I seem to have an initial allergic reaction to the pollen in the air and this seemed no different. On March 27, I felt a little worse, so that evening I called in sick for the next day. Over the next few days, both Vonnie and I experienced some symptoms of Covid-19, but I didn’t immediately think that we had it until I was notified by my hospital that the patient had tested positive. Before I got this news, when Vonnie had brought up the possibility that we may have “it,” I promptly shot down the idea, because as a clinical nurse, I felt that a temperature of less than 101 was unremarkable. Body temperature fluctuates throughout the day. We were taking our temperature every two or three hours, and only twice did I have a temperature greater than 100. Vonnie never had a high temperature.

My symptoms seemed to be more severe than Vonnie’s, and while during my illness I never felt that I was going to die or that I couldn’t breathe, I was unable to talk without immediately coughing. Those coughing fits seemed to have no end. One was so severe that it caused me to throw up. Other symptoms included night sweats and a pounding headache in the morning, for about a week. Vonnie’s symptoms were noticeably less severe, but they were still significant. My primary doctor, through a teleconference, abruptly shot down my suggestion that we might be positive when I told him what our temperatures were. But I was in contact with my supervisor and my hospital’s occupational health department, and on April 1, after describing my symptoms to occupational health, and requesting to be tested, they swabbed me in the tent. Upon returning from being swabbed, I received a call from my supervisor notifying me that I had been exposed, and two days later I received the positive result.

After three weeks I was on the mend and was eager to get back to work. I had heard that several of my coworkers had been exposed and were out of commission. Despite my desire to return to work, my primary doctor would not release me to work until I had two negative swabs that were collected greater than 24 hours apart, per CDC guidelines. It took a few days before I was able to get authorization for two COVID tests due to the statewide shortage. After a few more days and two negative tests, I returned to work and was happy to be back.

Since the day that I was first exposed, visitors have not been allowed in the hospital. Over the last 12-plus years that I’ve been a nurse, I have grown to understand the importance of having a family member at the patient’s bedside. I often tell them that it is the single most important factor in ensuring effective care. The nurse often has three to four other patients to care for and the family member at the bedside is only focused on their loved one. They also know the patient’s baseline behavior and demeanor and are more likely to pick up on subtle behavioral cues or changes. They are an extra set of eyes and ears for the nurses and I greatly appreciate their presence, and I let them know it.

Family members can sometimes be a hindrance to delivering care, true. But the comfort for the patient far outweighs any minor annoyance. This pandemic has made this strikingly clear, and I feel for my patients. Being in the hospital is isolating enough without having your friends and family barred. Wearing a mask for 12–13 hours at a time with only a few breaks here and there has not been easy, and I can tell that it impacts how I deliver care. When I perform my initial physical assessment on my patients, I often slip in a joke to lighten things up, but with the mask on they are unable to see me smile. The mask restricts the visual warmth I wish to convey with a smile, and it casts a thin layer of sterility throughout the room—and not the good kind of sterility.

At the beginning of our trip, leaving Flagstaff early in the morning, we went through a fast food drive-through. In front of us was a man standing in front of the drive through window trying to order. He kept tapping on the window until someone finally opened it. We could see that he was trying to negotiate an order, but they would not let him, because, and I’m guessing here, he was a pedestrian standing in the drive through lane. After watching this scene and seeing the man walk back to his commercial transport truck, we realized that the size of his truck had prevented him from using the drive through lane. We felt for this guy and as we approached the window, we asked if they could add to our order what the gentleman had wanted. We would then surprise him with it. They couldn’t recall what he had wanted so we drove around to the driver, sitting in his truck, and told him we would buy it for him. We returned to the drive through lane and doubled his order. When we brought it to him, he expressed sincere gratitude. As we pulled onto AZ 89 heading north, we felt grateful to be in a position to carry out this small act of kindness. It was a sweet beginning to our trip.

These are strange times for all of us, and what I have learned in the last few months is that now, more than ever, small gestures, acts of kindness, and thoughtful consideration should be on everyone’s mind. I try to remind myself of this every day.

Richard Dooley is a nurse, designer, bartender, and entrepreneur. If you’re a margarita fan, visit him at https://market.tucsontamale.com/products/dicks-mix.

Category: TUCSON COVID TALES