Tucson COVID Tales No. 23: Teaching English on the Flat Screen, by Jennifer Makowsky

Not long before the pandemic hit, one of my students, Amir, walked over to me after class, holding out an Autozone advertisement for sun shades. “Teacher, what’s this?”

I took the ad. “It’s called a sun shade. It’s to make shade in your car.”

“Shade?”

I pointed out the window to a tree that cast a shadow across the front of the school. “Shade is the dark under the tree.”

He gave me a bewildered look, so I squinted up at the overhead lights. “It’s too bright,” I said, grabbing a notebook and holding it over my head to block the light. Once the light was out of my eyes, I gave an overexaggerated sigh of relief. “Like in Tucson, we need shade because the sun is so bright and hot.”

He nodded. “I understand.”

My job as a teacher of English as a Foreign Language requires that I speak slowly and clearly, punctuate my words with hand gestures, and pantomime different language concepts. Before COVID, I spent a lot of time drawing pictures on the classroom whiteboard, showing students photographs, and miming actions. It wasn’t unusual for me to fall to the floor to convey “faint,” stagger around to express “dizzy,” and imitate the Charlie Brown walk of dejection to suggest “sad.”

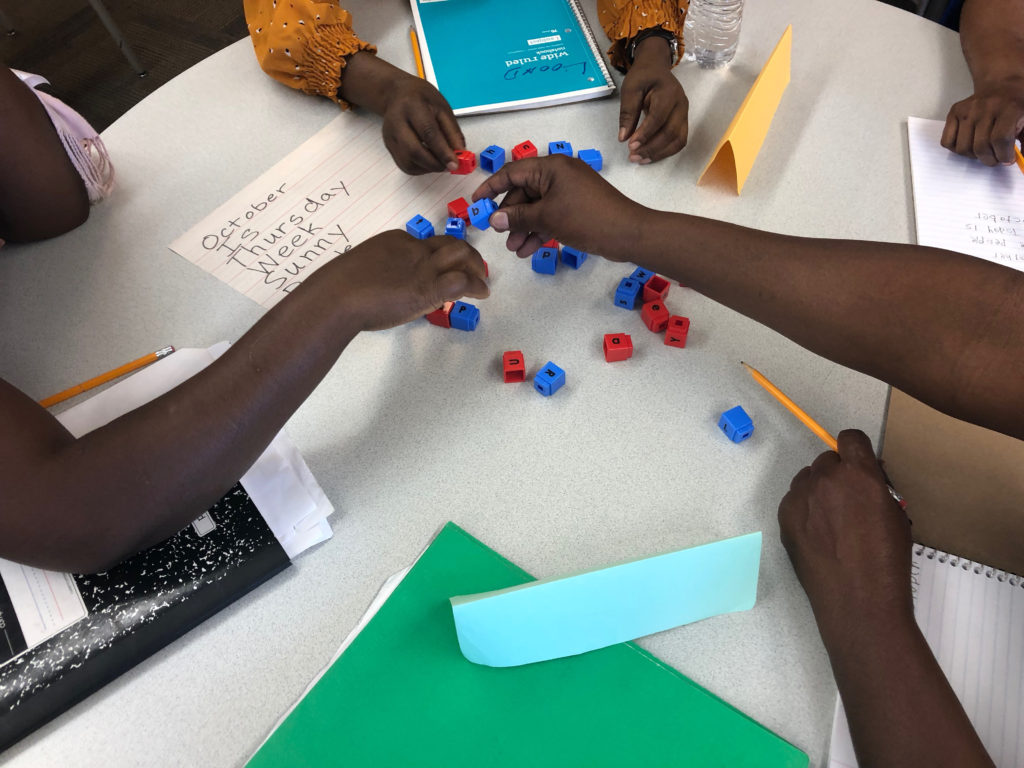

Where I teach adult English learners at Pima Community College’s Refugee Education Program (REP), the levels of English range from very beginning to advanced. One of the levels I teach is so basic that some students in the class do not know how to read in their native languages. A few have spent the majority of their lives in refugee camps and have never been to school. When we met face to face before COVID, I relied on body language and gestures to communicate with students. I think they had gotten used to me acting like a demented mime.

Then the pandemic hit. Suddenly all the three-dimensional classroom interactions were reduced to one-dimensional exchanges on a flat screen. Like teachers everywhere, the teachers in REP scrambled to figure out how we were going to teach from home. Most of our students do not have laptops or iPads, and several have limited computer skills. Nearly all, however, have smartphones. And nearly all of the students use WhatsApp in order to communicate with their family and friends back home in their native countries. When we still had a physical classroom, students often talked to family members before class started, using WhatsApp video chat. I’d often walk into the classroom and find a student holding the phone up and telling me to say hello. Suddenly a student’s mother or husband in the Congo or Syria was in my Pima classroom, waving. I never anticipated I’d be using WhatsApp to communicate with my students right here in Tucson. But here we are.

In the months since we left the brick-and-mortar building, I have been taking photos of things around the house, making homework packets, recording audio pronunciation practice, and filming my son acting out various verbs. My fellow teachers have been filming themselves baking, cooking, and helping to set up internet access for their students. We’ve been striving to keep students connected and engaged. When we had a classroom, we played games like Concentration and running dictation, went on scavenger hunts around the neighborhood, received visits from professionals in the community, and took field trips to the library and local businesses. Now I meet students through WhatsApp chat. My former laughter-filled classroom has been reduced to my laptop and phone in the silent guest room at the back of my house.

Having said all that, this virtual time with my students has allowed me to connect with them in a different way. When I’m not talking to students on the phone or using chat in WhatsApp, I use the feature that allows me to video call students. I was hesitant at first because it almost felt invasive, but students welcomed me into their lives. When we video chat, I am transported to their apartments and houses and have come to know different family members. Students have answered my video calls at their jobs, from the hospital, the grocery store, from bed half-asleep, and even from the car wash. Once, Amir, who is a Lyft driver, tried to practice his English with me while driving. Naturally, I told him we better hang up before he had an accident. I forgot to ask him if he ever bought that sunshade.

Recently, when my mother was admitted to the hospital, my students flooded the class chat with pictures of hearts and sentiments like “May God heal your mother.” Amir sent a picture of the artificial flowers he keeps in his car to make it look nice for his customers along with a note that read: “I present these flowers to you for your mother.”

The threat of the pandemic has forced me to reach behind the scenes into students’ lives and has offered them more of a glimpse into mine. It’s given us a connection we might not have otherwise known. Yesterday, as I was video chatting with my student Sam, he laughed after I clapped out the syllables to difficult. “You always did that in class and it helped,” he said, imitating me clapping. “I hope we can continue this.”

A lump rose in my throat. His comment not only reminded me of how much I miss my students, but it had also pinpointed the feeling my students offer me—the feeling of being seen and appreciated. It’s one of the many reasons I love my job. Even outside the 3D classroom, Sam had remembered the clapping habit, and it had helped him. He wanted to continue it. Maybe things on the flat screen aren’t so bad after all.

Jennifer Makowsky is a writer, educator, and University of Arizona alum. She is an East Coaster by birth and Tucsonan by heart.

Category: TUCSON COVID TALES